How four men steered the national boat to freedom

They were the men who showed us the path to liberty. Imbued by the ideals of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, prepared to assume the leadership of the nation in his absence, they waged a necessary war for liberty.

It was in their hands that the fate of 75,000,000 Bengalis rested, their destiny to be moulded by these brave men who informed the world that even as the nation bore the brunt of organized military assault, they were there to help turn the tables on the enemy and therefore turn the tide.

One was truly academic in his bearings, in the gentleness he brought to his politics. One other was a socialist who dreamed of a future of equality and justice for his people. Another was a veteran in politics whose dedication to the national cause defined his links with his people. The fourth individual in this band of brothers was one whose parliamentary experience had solidified his democratic bearings.

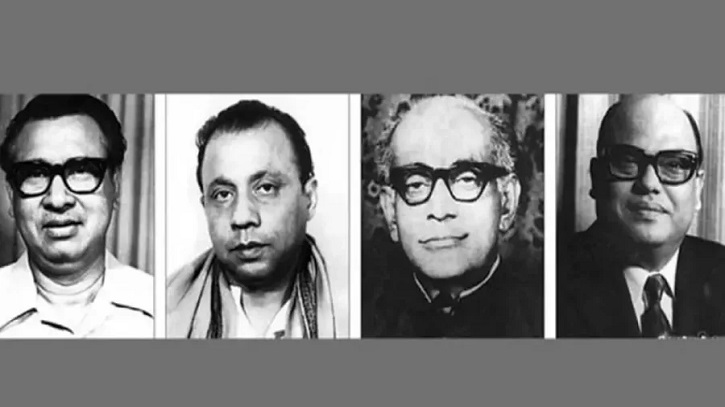

These men — Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmad, M Mansoor Ali, AHM Quamruzzaman — steered the national boat to freedom, despite all the odds and all the storms and all the villainy that came their way. They were the leaders who carried the lantern, flickering in the rain and in the rising winds, to inform us that dawn waited at the edge of the sinister, dark forest.

And then dawn came. These four men, these Mujibnagar men, these men constituting the very first Bengali national government in our part of the world, came home to us. They gathered us to themselves in the warmth which enriches history, gives it new meaning.

And then these four symbols of freedom died, were done to death, in the land they navigated to freedom. In a season of unmitigated horror, in circumstances most foul, they were shot and bayoneted to death in the supposed security of prison by their own Bengalis.

It is this undying shame we have lived with, this open wound we have inflicted on ourselves that does not heal, this outrage we have not been able to wipe off our collective conscience. As we basked in freedom, these inspirational leaders were felled in medieval bloodletting.

We let them die.

Barely hours after the assassinations, the killers were put on a flight out of the country, to Bangkok, with their families. Who was, or were, responsible for giving these murderers safe passage out of a disturbed country has never been known. It was one of those times when the nation waited for scraps of news; and no news came.

The men around the usurper who called himself president — all those cabinet ministers, that defence advisor, those elements who had said not a word when the assassins wiped out nearly the entirety of Bangabandhu’s family — did not call forth the courage to ask why the Mujibnagar men had to die.

All these timid, unscrupulous men were later to come up with a boxful of excuses to explain why they were not brave enough to protest the takeover of the state by rogue soldiers and their patrons in August, why they stayed meek when news came in of the killings in prison.

These were the men who, raised to prominence by Bangabandhu and serving under the Mujibnagar administration, chose to look the other way when their benefactors were silenced through the brutality of men with no souls, no decency in them.

All these decades have gone by since that annus horribilis made a mockery of our lives. All these years have elapsed since these four of our best and brightest died, barely three months into the bloodstained upending of the state on a dark dawn in August.

On the day these four leaders were done to death, the demand was made that they be interred within the mausoleum of the three leaders beside the university. That did not happen.

Why it did not happen has never been known. Why the usurper at Bangabhaban, once he had been shoved out of power, was left free, was not placed in prison, is a question we have not found answers to.

This morning, there are all the questions which well up in the soul, all the despair which rises in the heart. Where are the men, the rogue majors and rogue colonels and their rogue soldiers who carried out that macabre mission of murder on that fearsome November night?

Some of them have walked the gallows, for they killed the Father of the Nation. And yet there are the sepoys who, having done the killing, grow old in the spaces of this country. Who will engage in a mission to locate them, identify them and bring them to trial for the heinous crime they committed on that November night?

The killings of November 3 remain a tale that has not been fully told. There were the cohorts of the usurper, apart from the usurper himself, whose death from natural causes does not absolve them of guilt, of the right of the state to bring them to posthumous trial.

There is the moral requirement to ascertain the number of the assassins who made their way to Dhaka central jail on that night, their identities, their current whereabouts. It becomes necessary to identify the policeman who, once the assassins had left after their murder mission, called them back, to tell them that Tajuddin Ahmad was groaning and so was alive. These men of satanic intent returned. Their bayonets finally had one of the brightest of our stars close his eyes on the world.

These men were emblematic of greatness. Their work done in Mujibnagar, they went into the business of national reconstruction. They were ministers in Bangabandhu’s government. They were men who powered the engine of rebuilding and rehabilitation.

Their nationalism, resting on unadulterated secular belief, was their hold on democracy and on their belief in social order. They were the light in our collective life. They epitomized the belief in us, that surge of confidence in us after the trauma of mid-August, that they would return from the dungeon they had been pushed into to lead this land back to civilized order.

That was not to be. Intrigue moved faster than our belief, and coarseness laid our hopes waste in that season of criminality. Today, on this November morning, a breeze laden with old tragedy plays around the graves of these liberation leaders. Three of them lie one beside the other, silent for all time.

In distant Rajshahi, the silence of the fourth of these heroic men speaks of the glory that all of them brought home to us on a December day long, long ago. And we stand, heads bowed and hands folded and hearts breaking, in silent and enduring homage — to Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmad, M. Mansoor Ali and AHM Quamruzzaman.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is Consultant Editor, Dhaka Tribune

Source: Dhaka Tribune.